An Unconventional New Tool:

Dialogue Connects Readers with Suffering Children

By Pat Ford

Pew Center

“I’m hungry. When does the bread people come?” — Bobby, age 3

“Don’t you know a lot of people die here?” — Jimmy, age 10

“They’re taking our daddy away.” — Lovon, age 4

“Didn’t anybody ever tell you life isn’t fair?” — Angelica, age 4

These are the voices of the “Motel Children,” some of the hundreds of children living lives of deprivation in tourist-turned-residential motels across the street from Disneyland (“The Happiest Place on Earth”).

These are the voices of the “Motel Children,” some of the hundreds of children living lives of deprivation in tourist-turned-residential motels across the street from Disneyland (“The Happiest Place on Earth”).

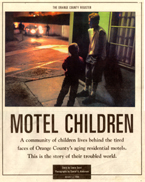

They starred in an extraordinary, 24-page special section published last August by The Orange County Register. Their story of poverty in the midst of affluence is told completely, and unconventionally, in their own words. Instead of writing a standard narrative, writer Laura Saari chronicled their lives and wrote the entire story using small vignettes and actual dialogue.

It was illustrated with award-winning pictures by photographer Daniel A. Anderson.

“It was the hardest story I ever wrote,” says Saari, “even though an editor said to me, ‘It looks like it’s not written’.”

Register editors launched the project nearly a year before it appeared. The idea had been to put a face on a troubling statistic: that despite a healthy local economy with low unemployment, one in five children in Orange County live in poverty.

Saari had stumbled onto the phenomenon of children being raised in residential motels while covering social issues and felt it would be a good vehicle for the project. About a third of the way through, she recalls, while briefing editors on the rich material she was gathering, executive editor Ken Brusic said, “Wouldn’t it be great if we could tell the story from the kids’ point of view?”

It sounded simple. It wasn’t. Saari wrote 25 drafts of the story, each time removing more of her own voice until the story seemed to be purely the voices of the children.

Project editor Kathy Armstrong had to resist Saari’s occasional, panicky urge to drop in the traditional journalistic three graphs of statistics about children in poverty. And she had to ignore her own concerns about telling the story so unconventionally.

“I was afraid people wouldn’t get it,” says Armstrong. “It was so different than most journalism. But when I listened to the phone calls the next day, I could tell: people got it.”

More than 1,100 people — some in tears — contacted the paper to offer the children support: $200,000 in donations, 50 tons of food, 8,000 toys and thousands of volunteer hours.

The county Board of Supervisors ordered an audit of services for motel children and directed $1 million in funds to create a housing program to get families out of motels. A non-profit agency launched a $5 million capital campaign for a shelter that would help motel families with drug abuse problems.

The city of Anaheim moved services into the motels so families would have easy access to parenting classes, job training and food programs.

“What’s been amazing to me,” says Saari, “is the way everyone is working together toward a solution.” A similar story told in a conventional way, Saari points out, would often put government agencies on the defensive. “But because of the approach we accidentally took,” she says, “no one felt they were being blamed. So instead of wasting energy defending themselves, they’ve hit the street.”

Engaging readers, activating public officials, improving life in the community — these are the loftiest goals of civic journalism, yet “Motel Children” did not set out to be a civic journalism project and did not use the tools and planning such projects often do. In this case, the story itself and the way it was told produced the results. Indeed, Saari may have discovered a new tool.

By removing herself so completely from the story, Saari enabled readers to feel as if they connected directly with the children. Description is offered in the same uncomplicated language the children themselves use, only to set the scene for the dialogue that follows, as in this section involving the Littlefield children, Angelica, 4 and Jeffrey, 6:

In the motel parking lot, the children are coloring a giant greeting card — WE MISS YOU COME BACK SOON — for two children who were taken away by the cops.

Angelica’s yellow dress puffs up around her legs when she sits. She pushes the dress down and it puffs back up.

“The cops took them because their mommy or daddy hitted them,” she tells her brother, Jeffrey. “The cops said: ‘You have to come with me,’ and they said, ‘Where are you taking me?’ And the cops, they didn’t say nothing.”

“The cops gave them ice cream,” Jeffrey says. His dad’s black truck goes by, headed out of the motel and Jeffrey runs after it.

The truck doesn’t stop.

Jeffrey collapses on a curb, crying.

“What’s the matter?” says his friend. “You don’t think your dad is coming back for you?”

Jeffrey kicks a stone.

“No,” he says.

Reporting the story was as challenging as writing and editing it.

Saari and Anderson started the project just as El Nino hit the West Coast with cold and rain that Orange County residents aren’t accustomed to. The optimum reporting time was three in the afternoon till after midnight, which meant a lot of cold, wet nights huddling outside motel rooms. They spent months building trust and relationships with the families they wanted to photograph and write about. And then their work would be undone by a rumor that they were undercover cops or social workers who were going to take the kids away.

“A lot of the parents had problems with addiction and you never knew whether they’d embrace you or slam the door in your face,” says Saari. “You’d have a relationship, you thought, but suddenly they’d shut you out.”

If parents decided they didn’t want their children identified, Saari used only first names.

Because they were focusing on children and teenagers, Saari and Anderson couldn’t approach their subjects as they would an adult. Anderson convinced Saari that the best technique would be to sit around while the children colored or played house or to bounce a ball with them and wait. Saari says she kept her notebook in a fanny pack and Anderson kept his camera under his shirt, so they would blend in, though they were always open about what they were doing. Sometimes hours would pass before anything would happen worth recording.

The story was emotionally draining, as well. Saari and Anderson worried about the children. Often, the only place for them to play was the motel parking lot, littered with broken glass, syringes, garbage and cars zooming through unmindful of the children. Most of the residents were single males — many of them fugitives, felons or drug dealers.

The children would miss weeks of school because of head lice. Saari worried about taking lice — or something worse — home to her own child.

“I still can’t talk about it,” says Saari, “without getting teary-eyed.”