Summer 2000

Stormy Weather Ahead

By Pat Ford

Pew Center

Just as sure as the sunshine and warm weather will bring tourists to Virginia Beach, residents of the Hampton Roads area of Virginia know, it will also bring storms, hurricanes and, by August, the threat of major floods.

Situated at the junction of the Atlantic Ocean and the Chesapeake Bay, the area is extremely vulnerable to storms. And for The Virginian Pilot, bad weather is a major story.

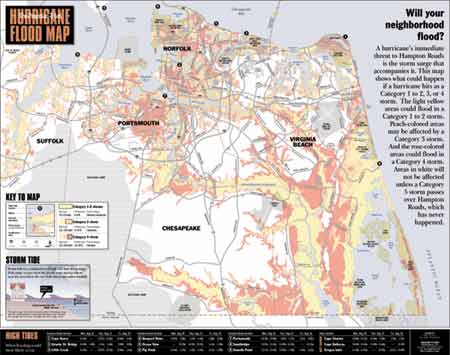

The paper doesn’t even wait for a storm to hit. Just before hurricane season starts in earnest, The Virginian-Pilot runs a special section with tips for staying safe, protecting your home and, across the double-truck of its center page, a map of the entire area, color-coded to show which neighborhoods are most likely to flood and by how much.

“We could run a list of areas that are flood prone,” says public safety editor Bill Burke, “but that doesn’t really capture it as effectively. Nothing does it as well as that map.”

The map shows major roads and landmarks in the five towns in The Virginian-Pilot’s coverage area. In bright yellow are the places likely to flood in any hurricane. They include the southern coastline, not surprisingly, but also places unexpectedly far inland, along riverbeds and the Intracoastal Waterway. Peach-colored areas are likely to flood if a storm is bad enough to be declared a “Category 3” and reddish orange area are likely to flood if a storm produces winds over 130 mph. Using roads and landmarks as guides, readers can figure out whether they should evacuate or stay and hold down the fort.

Managing Editor Dennis Hartig says the idea for the map grew naturally out of the paper’s strategy of being “as locally meaningful as possible.” The paper wants to deliver not just the news, says Hartig, “but what it means to you and your community.

“That’s actually the way we think,” he says. “How can we be more helpful in getting people the information they need to make better decisions.”

Hartig says the paper has gotten a lot of reader reaction since it started running the map two hurricane seasons ago and it is overwhelmingly positive. “We get the comments we hope to get,” says Hartig, “that is, high utility. It’s really useful. It has a lot of information.”

Hartig says it took a lot of time and expense to figure out how to take information about flood areas provided by the Federal Emergency Management Agency and translate it into a readable map with colors that contrast enough to show the range of risks.

“But it’s a huge public service,” he says. “You can’t get more local than: Am I going to be flooded out? Am I going to be able to get to work? Am I going to be able to get home?”

Hartig credits creative director Eric Seidman with designing a map that allows readers to answer those questions.

“We consider it a failure,” says Seidman, only a little jokingly. Though he is proud of what is there, Seidman says he is far from satisfied and that he and other staff members continue to work on making the map even more useful.

Eventually, Seidman says he hopes to provide even more detail. He wants to do five or six separate maps, one for each of the towns in the Hampton Road region. That way, he can include more streets that will help readers determine their own flood risk even more accurately.

Hartig says the paper also wants to include the impact of rainfall, not just the tidal surge projections in the current map. When Hurricane Floyd hit last fall, the winds had dropped and the area was spared the storm surge. But what Hartig describes as “biblical amounts of rain” caused flooding in one nearby town that left residents without water for three days.

Seidman says he considers the flood map an example of one of the most important things the newspaper can do. “The last bastion for newspapers is the ‘linger factor’,” says Seidman. “We can run a flood map and you can scrutinize it. Then you can put it away and pull it back out again when you need it.

“This is one of the very few areas left where newspapers hold true value for their community.”